Beijing reflects on its losing bet on the Assad regime.

By James Palmer, a deputy editor at Foreign Policy.

After the rapid collapse of the Syrian government on Sunday, China is likely to reflect on its losing bet on President Bashar al-Assad’s regime. But when the dust clears, new leaders in Damascus may be looking for reliable allies.

China has been aligned with Assad since Syria’s civil war began in 2011—but largely through its close ties to Russia and Iran, which backed the Syrian leader. At the United Nations, Beijing has often voted in lockstep with Moscow, blocking condemnations of Assad as well as cross-border aid. China significantly reduced its presence in Syria amid the conflict, though it kept investing in the country.

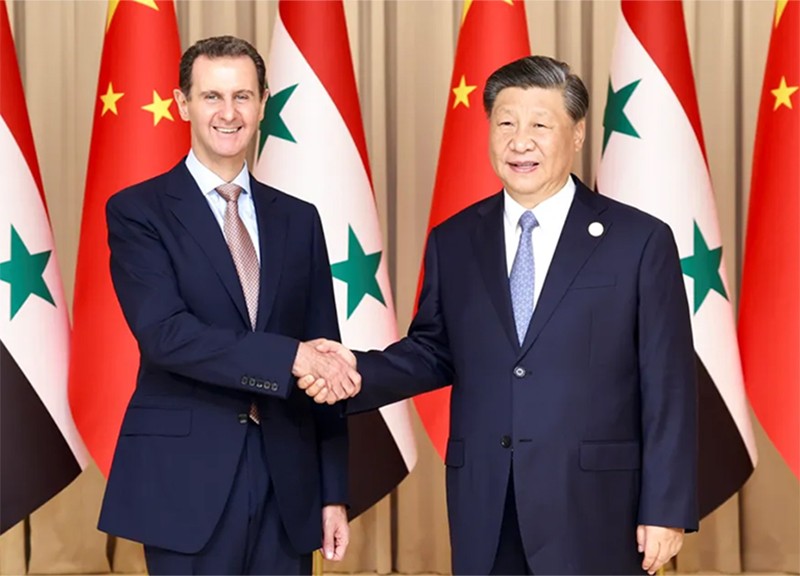

Chinese President Xi Jinping met with Assad in Hangzhou ahead of the Asian Games last year. At the time, China believed that the Syrian government was nearing a clear victory in the civil war. The two countries elevated their ties to a “strategic partnership,” but further investment was slow to come. (Syria joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2022, but it has not hosted a single project.)

Like the rest of the world, China was caught off guard by the speed of the rebel advance in Syria since late last month, led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). Last week, Chinese experts on the Middle East were still predicting a long, drawn-out war in Syria—as the ChinaMed Project has usefully covered.

Chinese discourse on the Syrian civil war was previously somewhat triumphalist. Many analysts suggested that Beijing’s support for Assad was justified by his regime’s seeming victory, and there was also praise for the “tide of reconciliation”—a favorite term of Chinese state media—that supposedly flooded the Middle East in the aftermath of China’s successful negotiation of Saudi-Iranian rapprochement last year.

The experts and officials involved will now look for an explanation for the hollowness of Assad’s regime and the success of the rebels. There is real expertise among Chinese academics on the Middle East, but there is also a tendency among Chinese officials to jump to conclusions, such as blaming the CIA for so-called color revolutions.

One immediate concern will be the safety of Chinese nationals in Syria, whom Beijing is already encouraging to leave the country. It’s not clear how many Chinese citizens are in Syria, given the cautious approach to investment there.

In 2011, China evacuated 35,000 of its citizens from Libya amid conflict there. A similar operation in Syria is possible—but it is unlikely unless the situation deteriorates rapidly or Xi decides that it could offer a propaganda opportunity. (Numerous Chinese movies glorifying the military have focused on the Libyan operation, most notoriously the massive hit Wolf Warrior 2.)

Beijing’s other big concern will be the presence of Uyghur fighters among rebel forces in Syria. Estimates of their numbers range from the hundreds to the thousands. China will prioritize putting pressure on Syria’s new rulers to exclude these fighters from any role in government and ideally to deport them to China. That may be tricky, since the Uyghur militants have a working relationship with HTS.

Yet any new leadership in Damascus will also probably be keen to build a relationship with Beijing. Syria has lost 85 percent of its GDP over the course of the war. A first step to solidifying ties may be protecting Chinese assets; it is possible the Uyghur fighters may end up as sacrificial pawns.

Meanwhile, Chinese outreach to HTS will probably pass through Turkey, which has considerable ties with the militant group. But Beijing is ideologically flexible enough to accommodate almost any government that emerges from the ashes in Damascus.