Epic Construction Site in the Saudi Desert Is a Hazard for Workers

By Rory Jones and Eliot Brown. WSJ.

Billed as a futuristic city-state with dazzling architecture including parallel 106-mile-long skyscrapers taller than the Empire State Building, Neom is the centerpiece of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's plans to transform his oil-rich country into a modern diversified economy.

But for its 100,000 workers, the world's biggest construction project has been more like a dystopia.

Neom employees have reported incidents of gang rape, suicide, attempted murder and drug dealing on the site, slated to cover an area the size of Massachusetts. Last year, a McKinsey consultant died in a head-on crash at night even after safety staff warned Neom management about the danger of driving late on the region's roads. Laborers at one of the migrant worker camps mounted a violent protest over frustration with food. Children as young as 8 have been caught driving trucks.

Current and former Neom staff say the incidents illustrate what can go wrong when so many people arrive in an isolated part of the world to build a highly ambitious project on an unrealistically aggressive timetable. Neom is set to face even greater scrutiny as soccer’s world governing body this month appointed Saudi Arabia host of the 2034 FIFA World Cup, with the project expected to build one of the major stadiums for the event.

Neom has made an effort to set high standards for the accommodation for blue-collar workers, current and former employees said, conscious of the bad publicity around big Gulf construction projects for events such as the 2022 World Cup in Qatar.

“Protecting the welfare of those working on-site is a top priority,” a Neom spokesperson said. She added that contractors and third parties have to comply with Neom’s welfare standards, and that Neom investigates inappropriate workplace behaviors as well as any allegations of wrongdoing or misconduct. Neom’s safety management system is based on international standards and audited by the British Safety Council, a U.K.-based nonprofit, she said.

The Saudi government, which owns the Neom project, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Cost overruns, staff turnover and a culture of bullying and harassment have plagued the project, The Wall Street Journal has reported. Neom Chief Executive Nadhmi alNasr abruptly left last month, following two other senior executives who were the subject of a Journal article that highlighted the inappropriate workplace behavior.

White-collar workers began moving to the site on the edge of the azure shores of the Red Sea—over two hours from any city of a decent size—in 2020. Since then, clusters of modular housing compounds have sprouted packed with workers, giving the project many of the problems associated with a small city but without the mechanisms to deal with them.

High risk

Current and former employees say there is a lack of investment in emergency services needed to keep any city safe. An independent report commissioned by Neom in 2022 said the state of emergency services at the project exposed its employees, contractors and reputation to what it called catastrophic risk.

“There is no evidence of a single cohesive strategic emergency plan covering the whole of Neom,” wrote Serco, a British security, healthcare and transport company. Interviews with emergency services personnel show the gaps have yet to be filled.

Serco, in a statement, said it had witnessed firsthand how safety standards both at Neom and across the kingdom have advanced since its 2022 report.

Neom’s employees have worked to improve the situation, implementing training programs with contractors to avoid work-related accidents and a road-safety campaign.

Construction deaths—a feature of any megaproject—have been relatively sparse. Neom reported eight workplace fatalities last year, according to a list of deaths in 2023 reviewed by the Journal. That puts the project’s safety record roughly on par with the construction industry in the U.S., which reported 9.6 deaths per 100,000 employees in 2022, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Former employees caution the tally could be higher, because some deaths likely go unreported.

Neom now has a hospital on site as well as a separate healthcare clinic and ambulances and helicopters for medical emergencies and rescue, according to current and former employees familiar with the project’s improvements.

Still, the project continues to have trouble preventing and responding to accidents. In one week in November, Neom reported five fatalities at workplaces and on the roads, current and former employees said.

“It is still the Wild West,” said one employee.

Prince Mohammed began thinking about Neom nearly a decade ago. The young prince, eager to open up his conservative Islamic economy to the world, zeroed in on Saudi Arabia’s barren northwest to build a more liberal society unshackled by social strictures in the rest of the country.

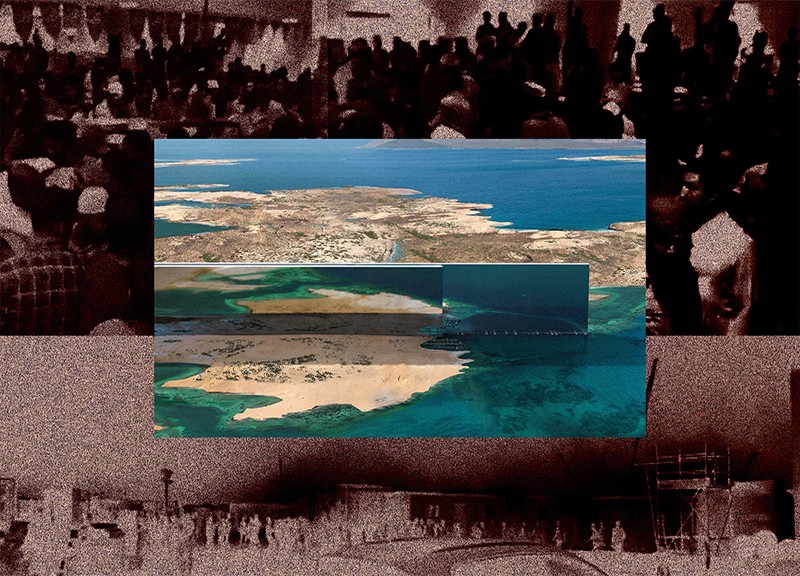

The area had many ingredients to make the project a success: rugged mountain landscapes, untouched beaches and coral reefs, and generally cooler temperatures than the rest of the desert kingdom. In a January 2017 Neom board meeting, the prince said he wanted to turn the region into the largest city globally by GDP, according to planning documents previously reported by the Journal.

While remote, Saudi Arabia’s northwest wasn’t totally a blank canvas. The region was home to about 20,000 members of a Saudi tribe known as the Huwaitat, who pushed back against the prince’s plans.

One member of the tribe, Abdulrahim Ahmad Mahmoud al-Huwaiti, launched an online campaign critical of the government. In 2020, Saudi security services forcibly removed the Huwaitat from towns earmarked for demolition, shooting dead 43-year-old Huwaiti, saying he opened fire from his home. Saudi security forces detained and sentenced two dozen other Huwaitat for terrorism offenses and five now face the death penalty, according to Saudi human rights organization Al Qst.

It was an inauspicious start for a project that markets itself as an “accelerator of human progress” and seeks to attract foreign talent and capital.

Most of Neom’s white-collar employees were then working from an office in Riyadh, the Saudi capital. In October 2020, Neom relocated 450 white-collar staff to live permanently at Neom, housing them in a temporary camp with portable cabin accommodation and a food hall for residents. People regularly ate together, and former employees and consultants describe a spirit of camaraderie in the early days—a sense they were part of an exciting project in an untouched frontier.

On weekends, people hiked desert trails or scubadived off the region’s beaches, chatting in-between dives while sitting on the tailgates of their SUVs. While socializing at a beach in 2021, the lead executive at U.S. design and engineering firm Aecom’s Saudi unit died trying to help rescue another person who was drowning in the sea, according to former employees and a person close to the executive. Neom banned scuba diving for a while after the death, said former employees aware of the death.

At the time, emergency services were fragmented among different government organizations across a vast area and accustomed to meeting the needs of a Saudi population of only tens of thousands. The nearest major hospital was in Tabuk, about two hours away, former employees said.

As the region’s population swelled, road safety proved a challenge. Driving in the region is a white-knuckle affair. Former employees are quick to volunteer anecdotes of times they swerved to avoid near crashes with trucks and oncoming cars careening around curves.

Current and former employees said they saw Saudi children driving vehicles servicing the project’s subcontractors. In 2021, an 8-year-old Saudi boy driving a water tanker hit a pickup truck carrying two people working at Neom, according to a former publicsafety employee. One persondiedat the scene, another later succumbed to their injuries and the boy survived, the former employee said.

Serco, in its 2022 report, said the “greatest danger to personal safety across Neom” was connected to the use of motor vehicles, citing their lack of roadworthiness, a failure to comply with regulations, and unqualified drivers working illegally. The report’s authors said people drove vehicles the wrong way along highways, cut across the median, and overtook beyond the maximum permitted speed.

Enforcement of the law was minimal, the report said. Its authors witnessed police units drive past a two-vehicle collision without stopping and noted how a tractor that crashed into a median outside police offices remained there for weeks.

Neom at the time launched a road-safety campaign, but staff still suffered fatal accidents. In September 2022, three Neom workers died after driving their vehicle off an unfinished highway, according to an internal Neom report of the incident. The vehicle was driving at high speed “when it left the road surface,” ejecting two passengers who weren’t wearing seat belts.

The report suggested Neom conduct a survey of dead-end roads to avoid a similar incident. It made wider recommendations, including providing company transportation for those traveling at night or after working more than eight hours.

The following year, a McKinsey consultant died in a head-on-collision at night, according to a Neom report on the incident. Two passengers in the car were taken to the hospital and the driver of the other vehicle also died, the report said.

A McKinsey spokesperson said the company remained “deeply saddened by the tragic road traffic accident.”

A person familiar with the incident said the McKinsey consultant was driving to a hotel. At the time, some consultants working for Neom were commuting to the project from hotels in Tabuk—two hours’ drive away—due to Neom’s isolation and a shortage of suitable housing, former employees and consultants said.

Neom has also grappled with where to house workers and create an emergency services system equipped to manage the influx of people.

Much of Neom’s permanent real estate is years away from completion, so Neom has constructed three more temporary housing locations for its whitecollar employees. The largest, called NC1, has the look of a movie set of a suburb, where rapidly built modular homes are lined by sidewalks and palm trees. There are schools, a Dunkin’ and a Hampton by Hilton. Workers post social media of their Starbucks iced lattes. They play tennis in the cool evenings, swim in the pools during the day and stay fit in the gym. Current and former staff describe life for white-collar workers as simple but comfortable.

Migrant workers

The Neom project’s population is dominated by migrant construction workers from Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines and elsewhere. In the mornings, they hop into buses and trucks and head to work in air filled with dust and diesel fumes to excavate the twin skyscrapers, known as “The Line,” or take winding roads to work at a ski mountain. For work on Neom’s island resort, workers in hard hats and neon orange vests line up by the thousands to pack on to ferries made for vehicles—but converted for passenger use with a precarious makeshift barrier of wire fencing.

For housing the blue-collar workers, Neom largely outsourced the work to Saudi subcontractors and established a welfare team to oversee the quality of accommodations. Social-media videos show workers lounging in their fourperson air-conditioned rooms, eating curry in the cafeteria and playing cricket in athletic fields.

The increase in housing, however, hasn’t kept pace with tens of thousands of migrant workers arriving at the project.

Neom’s staff last year logged 168 camps that were built unofficially or didn’t meet the project’s standards, former employees said. These camps, housing anywhere from a few people to hundreds, were overcrowded, lacked amenities or weren’t providing food or security, former employees said. Workers frequently slept in their trucks, and some inside Neom-regulated camps would hand passes to workers on different shifts to sleep in the same bed.

Public security at the migrant-worker camps has also proved a concern. Serco, in its report in 2022, said Neom lacked sufficient numbers of security staff, and those it did have were poorly trained and ill-equipped. The capability of the Saudi police wasn’t sufficient, “and certainly not for the scale and speed of future development.” the report said.

That year, 12 security guards from different camps brawled, leaving one person unconscious after an attack with a rock, former employees said.

In March last year, laborers mounted a violent protest—a rare occurrence in Saudi Arabia —over the quality of food at a Neom-regulated camp, according to videos viewed by the Journal. The workers initially threw utensils and serving trays at the chefs before hurling debris at buildings.

A month later, medics at a camp treated a migrant worker for a drug overdose. Neom staff searched the worker’s room and found bags of what appeared to be methamphetamines being sold to colleagues, according to an image of the bust viewed by the Journal.

Violent crime

Based on medical reports at clinics in worker camps, Neom staff have documented instances of gang rape, attempted murder and suicide, according to a summary of incidents viewed by the Journal. One worker slashed his wrists complaining that he wasn’t being paid, according to the report.

Former Neom employees said the frequency and severity of incidents was hard to ascertain because Neom staff only logged reports at medical clinics and hadn’t actively policed the camps or investigated issues.

The chaotic environment at Neom’s worker camps has extended at times to its job sites.

A spate of workplace fatalities last year prompted then-Chief Executive Nasr to host an all-hands meeting with white-collar staff where he vowed to improve the situation, according to employees who were in the room. At the meeting, staff were all asked to sign a white board with a message making a commitment to safety, these former employees said.

According to a list of deaths in 2023 that was reviewed by the Journal: One person died after mishandling explosives. A tunnel collapsed on one person, and a wall on another. One worker died after a tanker backed up into him.

One of those who died a few months after the all-hands meeting was Abdul Wali Khan, a 25-year-old worker for China Communications Services, a Neom subcontractor. He died last December when a metal gate being installed at Neom’s healthcare center fell on him, according to a Neom list of workplace fatalities.

His brother, Meer Wali Khan, said he struggled for weeks to repatriate Abdul’s body to Pakistan. The body was transported to a hospital in Tabuk, but staff there refused to release it, because there was no police report of the incident, Khan said.

Khan said China Comservice couldn’t explain why there was no police report, telling him that Neom was responsible for logging the death rather than the police. Eventually Comservice, which didn’t respond to requests for comment, wrote an incident report that Khan took to the police who then issued a letter for the hospital, Khan said.

“Even until today I haven’t seen CCTV footage,” said Khan, who wants to better understand his brother’s death. “It makes you think something is wrong.”