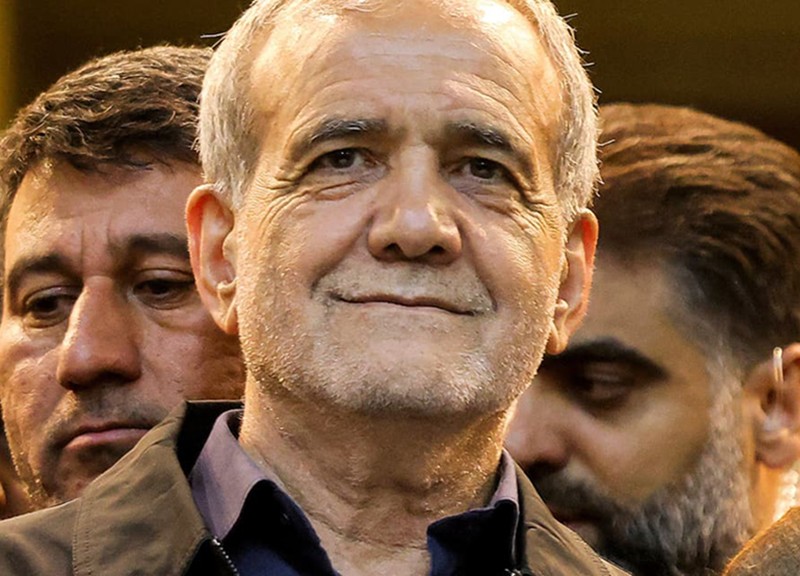

President-elect Masoud Pezeshkian is a kinder, softer regime loyalist. Khamenei and the Islamic Guard Corps still rule.

By Reuel Marc Gerecht And Ray Takeyh, WSJ

The accidental death in May of Iran's President Ebrahim Raisi, a cleric of unwavering loyalty to the Islamic Republic's supreme leader, obliged Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to call for a new election. Mr. Khamenei surely views presidential elections with trepidation. They have for three decades routinely revealed the Iranian electorate's distaste for him and the theocracy that actually controls the government. The regime now rigorously vets candidates to ensure that convulsive political movements don't arise.

In many quarters, the victory of the relatively moderate Masoud Pezeshkian is seen as a rebuke to a system that had come to rely exclusively on reactionaries. That view is mistaken. The Islamic Republic is stronger than it was before the election. The supreme leader, who can prevent anyone from running for of fice and unquestionably rigged the 2009 presidential election, will likely benefit from having a president who is a physician rather than a dour, uninspiring mullah.

Mr. Pezeshkian is a familiar politician in Iran. He has spent his public career on the periphery of power. A former surgeon, he had a long stint in Parliament that yielded little in the way of practical achievement. He was a health minister, head of the weakest Iranian bureaucracy. Unlike former Presidents Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Hassan Rouhani, he was never an insider, privy to the regime's secrets and aware of its trapdoors. Since the office of the supreme leader has absorbed many of the powers of the presidency, Mr. Pezeshkian will have limited maneuvering room.

The Western press refers to Mr. Pezeshkian as a reformer. But this political category no longer exists. The reform movement evolved in the early 1990s as an eclectic group of intellectuals, politicians and religious leaders who sought to reconceptualize the Islamic Republic. Their essential argument was that the elected institutions were more important than the theocracy. Although loyal to the revolution, the reformers challenged the position of the supreme leader, whose absolutism they claimed contravened the democratic spirit of the revolution. The high point of the reform movement came in 1997 with the presidential election of Mohammad Khatami, who, though loyal to the idea that the people occasionally needed supervening clerical guidance, sincerely wanted more democracy in the system.

The hard-line backlash was swift and successful: Mr. Khamenei and the always-loyal Revolutionary Guards eviscerated the reform movement. Today, reformers are leftists stripped of lofty aspirations. They call for greater cultural tolerance, economic efficiency and a less confrontational foreign policy. Their rhetoric and actions often haven't aligned.

Throughout the campaign, Mr. Pezeshkian stayed within these modest parameters. He spoke of his respect for Mr. Khamenei and his mandates. He talked of a national unity government and the need for technocrats. His first act as a newly minted president was to pray at the mausoleum of the founder of the revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

The kinder, softer Mr. Pezeshkian isn't without his uses for the supreme leader. The genius of the Islamic Republic is that it contains within its authoritarian structure elected institutions that have little power but still provide the public a means for expressing grievances. Mr. Khamenei had all but shut down this safety valve in the past few years with his relentless purges and his engineering of Raisi's promotions. The death of his protégé offered an opportunity to recalibrate a system that has badly needed tinkering.

Paradoxically, Mr. Pezeshkian may owe his presidency to the Women, Life, Freedom protest movement that the regime took too long to put down in 2022. During the crisis, when many in the mullah's inner circle went wobbly, Mr. Pezeshkian proved his mettle and fidelity to Mr. Khamenei. "This situation only benefits the hypocrites and enemies of the Iranian people, who seek to sow turmoil and unrest and widen the gap between the people and the government," Mr. Pezeshkian said at the time. He was more measured during the campaign and pledged to uphold women's rights. For a populace whose rebel- lion simmers more than it boils, Mr. Pezeshkian could prove a sufficient, albeit temporary, tranquilizer.

Since Mr. Pezeshkian has spoken positively of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action-aka the Iran nuclear deal-expect Westerners to cross their fingers hoping he'll restart secret negotiations. But the bomb project is the domain of the supreme leader and the Revolutionary Guards, who have shown little interest in once more transacting an arms-control agreement with perfidious Americans. The program is now too far advanced and the lure of sanctions relief too unattractive to tempt Iran's real leaders to trade carrots for uranium. The wheels of diplomacy will spin but yield nothing.

Much has changed since the nuclear agreement was made in 2015. The Islamic Republic stands with Russia and China as they assault the established world order. Tehran has benefited greatly from this alliance through sanctions-proof trade with Beijing and arms from Moscow. In the Middle East, Iran's axis of resistance has extended its imperial reach. The Islamic Republic is now the most important power in the region because its lethal allies have mauled Israel, hobbled Saudi Arabia and humbled America.

These are historic achievements. Mr. Khamenei isn't going to concede this progress. He may not even change his tone to enable the new president's goodwill diplomacy to seduce Westerners, who, allergic to more wars in the Middle East, always seem ready to give the clerical regime another chance.

Mr. Gerecht is a resident scholar at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Mr. Takeyh is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.