It’s too early to celebrate Assad’s departure as Erdogan’s victory.

By Steven A. Cook, a columnist at Foreign Policy and the Eni Enrico Mattei senior fellow for Middle East and Africa studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Since Bashar al-Assad’s fall in mid-December, a variety of foreign-policy analysts and journalists have declared Turkey “the winner” in Syria. It is a narrative that Turkish officials and their supporters have advanced in both ham-handed and worrying ways. But is it true? No. Or at least, Turkey has not won anything yet.

It is true that Turkey is in an advantageous position in Syria. Ankara’s patrons, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the amalgam of militias called the Syrian National Army, were responsible for the end of the Assad regime. Turkey’s proximity to Syria and the well-known Turkish expertise in infrastructure development will also help firms that are well connected in Ankara to win reconstruction contracts.

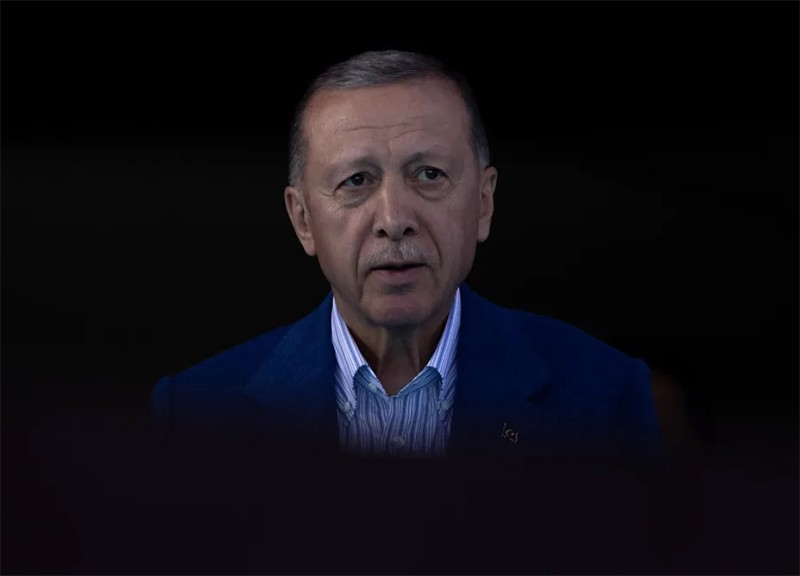

Yet President Recep Tayyip Erdogan confronts major obstacles to establishing himself as the external powerbroker in Damascus.

Much of the claim that Turkey won Syria hinges on the fact that HTS and the Syrian National Army militias spearheaded the fall of Aleppo that led to Assad’s flight from the country that his family dominated for half a century. But things are not always what they seem to be. The Turkish-approved attack on Aleppo that began in late November was intended to be limited. Rather than the fall of Assad, Ankara’s aim was to pressure the then-Syrian president to negotiate Turkey-Syria normalization—a goal that the Turkish government had pursued for the prior two years. It was only when the Syrian military collapsed that the Turks revised their policy, claiming that Bashar’s demise was always their plan.

Not long after HTS liberated Damascus, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan appeared in the Syrian capital, where he figuratively and literally embraced the HTS. (As an aside, the irony of Turkey’s public claim to patronage of HTS was too much for anyone who remembers the vicious prosecution of intrepid Turkish journalists who uncovered Ankara’s coordination with this al Qaeda offshoot—an exchange that was directed by then-intelligence chief Hakan Fidan.)

The Turkey-HTS partnership was obviously productive, but the idea that Ankara is victorious in Syria assumes that the Turkish government has all the power in this relationship. It likely once did, but after the end of the Assad regime, HTS needs Erdogan and company less.

Although Fidan beat everyone else to Damascus, a parade of delegations also beat a path to HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa’s doorstep, including diplomats from the United States, United Kingdon, and France and Germany (collectively representing the European Union). Iraq’s intelligence chief made the trip to Syria. Representatives of the Syrian leadership have also been reaching out to its neighbors. The transitional foreign minister, Asaad Hassan al-Shaybani, has visited Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; Doha, Qatar; and Amman, Jordan. Clearly, al-Sharaa has more options for external partners than he and HTS had just two months ago.

Turkey is not out of it, of course, but the efforts of major Arab states to establish contact and a working relationship with Syria’s new leaders highlights a Turkish weakness in the region: Leaders in Ankara claim to have a cultural affinity with Arab countries that gives them unique insight into Middle Eastern societies. It is a mostly empty claim based on their (mis)reading of Ottoman history. To be sure, over the years polls have consistently demonstrated that Erdogan is popular primarily due to his support for Palestinians, there are a fair number of Arab tourists in Istanbul, and Middle Easterners have a demonstrated fondness for Turkish television soaps—but that hardly constitutes cultural affinity.

It is more likely that as Islamists, Erdogan and the ruling Justice and Development Party have a yen for the Arab world, especially their fellow Islamists among the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas, and others. Regardless of whatever affinity Turks may perceive between themselves and Syrians, it likely pales in comparison to that of Syrians with their fellow Arabs. This gives Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Jordan, and others an advantage over Turkey in Damascus.

Then there is the thorny issue of Kurdish nationalism and the Syrian Kurdish fighting forces called the People’s Protection Units (YPG), which has formed the core of Washington’s partner against the Islamic State in Syria, the Syrian Democratic Forces. The Turkish government believes that with the end of the Assad regime, HTS in power in Damascus, and U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s previous willingness to withdraw American forces, there is an opportunity to use the Syrian National Army to destroy the YPG, which it does not distinguish from the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)—a designated terrorist group. This would, from Ankara’s perspective, finally rid it of a security threat from the south.

From Turkey’s perspective, it does seem to be a propitious moment to strike a devastating blow against Kurdish nationalism. And Ankara’s apparent victory in Syria seems to give Turkey the ability to accomplish this goal.

There are a few issues that complicate this straightforward scenario: First, the Kurds are not going to willingly accept their own destruction. They have the capacity to fight back, which presents Turkey with the unenviable prospect of having to fight guerilla conflict on two fronts—Syria and Iraq, where the PKK is holed up.

It is important to remember that even the mighty Turkish Armed Forces have been unable to finish off the PKK for more than 40 years. There is no reason to believe that the Turks and their Syrian allies could be any more successful. Second, HTS is not necessarily a partner in Turkey’s efforts to liquidate the Kurds. In a tangible sign that Turkish power in post-Assad Damascus is not what Ankara wants everyone to believe it is, Erdogan declared that he expected the new government to help him in its effort to destroy the YPG. This was an implicit admission of the limits of Turkish power in the Syrian capital.

The premature triumphalism around the idea that “Turkey won Syria” creates a set of assumptions and expectations that are not necessarily grounded in reality, setting policymakers up for potentially nasty surprises.

If policymakers take this narrative at face value, they will miss the subtle jockeying that is underway among regional powers for position in Damascus. This is just the next act in the prolonged drama over who controls Syria. No doubt, Turkey is a major protagonist with a lot of assets, but Ankara also has a fair number of liabilities. And it is important to remember that at every step since March 2011 when the Syrian uprising began, the Turks miscalculated, believing alternately that they could convince Assad to reform, induce the United States to overthrow the Syrian leader, and then use extremists toward that same end before giving up and seeking a rapprochement with Assad.

Of course, Ankara’s past mistakes in Syria do not mean that Erdogan will fail now, but it is way too early to declare Turkey the victor.