After years of war with the Houthis, Riyadh is seeking to ensure its security above all else—but peace talks are precarious, and the plan could backfire.

By Veena Ali-Khan, a Yemen and Persian Gulf researcher based in New York. Foreign Policy.

In the not-too-distant past, Saudi Arabia would have cherished the opportunity for a joint U.S.-U.K. strike targeting Houthi strongholds. After all, Riyadh fought a brutal war against the group for almost a decade. But today, a Western offensive on the Yemeni group is precisely the opposite of what Riyadh wants as it conducts a delicate peace negotiation with the Houthi leadership to extricate itself from Yemen and, it hopes, permanently protect itself from cross-border attacks.

As temperatures rise in the Red Sea, Saudi Arabia has therefore chosen to stay out of the conflict. Instead, the lines of communication between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis are staying open as Riyadh avoids overtly siding with Washington, lest it become the target of attacks. For now, this strategy seems to be working—but the larger question remains about whether this will guarantee Saudi Arabia’s protection in the long term.

Early on Jan. 12, U.S. and British warplanes targeted dozens of Houthi military sites in Yemen. A day later, Washington launched new raids on Houthi positions, targeting command centers, ammunition stores, missile launch systems, and drones. Vowing to take revenge, the Houthis fired ballistic missiles at a U.S.-owned container ship on Jan. 15. (Washington retaliated again on Jan. 16.)

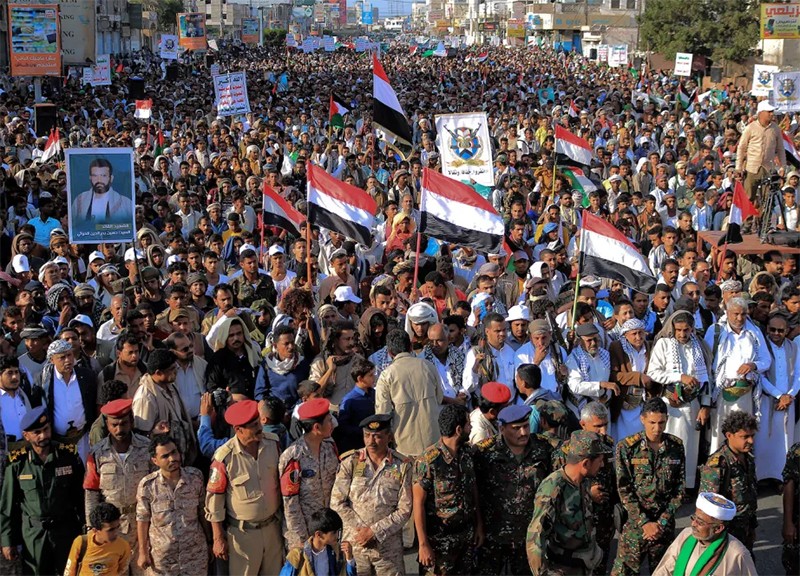

These strikes followed two months of Houthi attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea, which the rebels claim demonstrate solidarity with Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. The Houthis say that these strikes are limited to ships affiliated with Israel; in practice, they have targeted any vessels within range. At least 50 countries have been affected by the nearly 30 Houthi attacks on international shipping so far.

It did not take long for most of the world’s leading container-shipping companies to announce decisions to avoid the Red Sea, a vital waterway leading to the Suez Canal, which handles approximately 15 percent of the world’s shipping traffic and as much as one-third of all global container trade.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s recent Middle East tour was intended to pressure regional actors to keep the conflict in Gaza contained. However, Persian Gulf capitals know the Houthis—and their limited leverage over them—well, and they did not respond with much. In another attempt, the United States urged the Saudis to take the Red Sea crisis into consideration in their peace talks with the rebels and slow down their negotiations.

Nonetheless, both the Houthis and Riyadh opted to continue their discussions, preferring not to let the Red Sea crisis interfere with their progress. Following the U.S.-British strikes, the Saudi Foreign Ministry expressed its “great concern” and called for “self-restraint” to avoid an escalation.

Riyadh simply doesn’t have the appetite to embroil itself in another intractable conflict with the Houthis. The kingdom has learned from past lessons through dealing with the rebels militarily and is acutely aware that it risks falling directly in the line of fire.

The 2019 Aramco attacks that were claimed by the Houthis—which targeted two major oil installations and forced the kingdom to temporarily shut down half of its oil production—marked a turning point. This was due to the United States’ lack of response. Feeling betrayed by the Americans, Riyadh quickly recalibrated its foreign policy in the years that followed, seeking diplomatic solutions to its regional headaches instead of relying on Washington to come to its rescue.

These days, Riyadh is instead keeping dialogue open with Iran. A day prior to the strikes on Yemen, Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan was contacted by his Iranian counterpart, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian. The last thing that Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, needs is an escalation that disrupts the crucial years leading up to the much-anticipated Vision 2030, an extensive reform plan intended to diversify the national economy. Consequently, the kingdom opted to stay silent amid the Red Sea crisis, hoping that its communication channels with Iran—via a China-brokered deal announced in spring 2023—and the Houthis will shield it from regional turmoil and future Houthi attacks.

These new communication lines are not aimed at stopping Houthi actions in the Red Sea; rather, they are a pragmatic part of a wider effort to isolate the kingdom from any regional escalation, regardless of the circumstances. So far, the strategy appears to be working, and Riyadh has not been targeted. Indeed, part of Saudi Arabia’s decision not to join the U.S.-led maritime coalition against the Houthis is influenced by its experience of bearing the brunt of Iran-U.S. tensions.

Saudi Arabia’s number one priority is protecting itself. The kingdom wants a swift exit from Yemen’s war, and it won’t let the West’s latest spat with the rebels mess this up. Since 2021, negotiations with the Houthis—facilitated by Oman—have been snowballing. Riyadh has finally reached a point of effective communication with the rebels, something that took years to achieve. Hence, Saudi Arabia judges that it is not worthwhile to jeopardize this relationship—which the Saudis see as sufficient to protect themselves from Houthi attacks—just to support the U.S. operations in the Red Sea.

If anything, the recent escalation provided Saudi Arabia with additional incentives to finalize an agreement as soon as possible. Toward the end of November, Riyadh presented a draft proposal to the U.N. special envoy for Yemen, intended to lay the groundwork for future U.N.-led talks between the Yemeni government and the Houthis. Part of the agreement reportedly includes a buffer zone to protect Saudi Arabia’s borders, a top priority for the kingdom.

Riyadh is also feeling smug. The kingdom has long warned Washington about the dangers of the Houthis acquiring more advanced drone capabilities and gaining control of areas close to the Red Sea, but in their eyes, received only lackluster responses. Hence, Saudi Arabia is questioning why it should assist the same Western partners that have spent years criticizing it for its brutal war against the Houthis.

Now that Washington is in the Houthis’ firing line, Riyadh sees no reason to join it there.

But Saudi Arabia’s calculus could be mistaken. A final peace agreement has not yet been secured; what exists is merely a fragile understanding that could collapse at any moment. There is nothing stopping the Houthis from targeting the kingdom—in the Red Sea or its borders—in the future, absent an official peace agreement.

The likelihood of this possibility only increases as the situation escalates. The rebels themselves admit in private that Riyadh’s protection hinges on their decision not to engage in the wider spat. The Houthis are aware of Saudi Arabia’s weak point—its border—and can exploit this whenever they see fit. Just hours after the second spate of strikes made by the United States, the Houthis conducted a military maneuver along the Saudi border, serving as a warning to the kingdom about the potential consequences of siding with the United States.

Complicating matters further, if and when Riyadh decides to resume normalization talks with Israel, the kingdom could once again become a prime target for the rebels. The Houthis have not shied away from voicing their criticism of the Abraham Accords—the U.S.-brokered deal that normalized relations between Israel and some Arab nations in 2020—and this issue has been central to their critique of the United Arab Emirates.

Should Saudi Arabia proceed with normalization talks, there’s a strong possibility that the Houthis might shift the goal posts and declare their intent to target any nation perceived as aligned with Israel, using it as justification to extract further concessions from the Saudis on the peace talks. What is for certain is that Riyadh will need to resume talks with Israel while being mindful of potential future targeting by the rebels.

In an ideal world for the warring sides, their peace talks would remain compartmentalized from the Red Sea crisis. But this is not the reality of today. The region is quickly heating up, and more actors are entering into the fray by the minute that could altogether threaten Yemen’s fragile peace process. If the United States opts for nonmilitary approaches—such as designating the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization—Houthi participation in future U.N.-led peace talks will be compromised, raising the specter of reigniting the local conflict in Yemen and thus ending the de facto truce.

On the other hand, if the United States and Britain continue to strike Yemen, the Houthis could escalate further, as they have threatened to do, by targeting U.S. military bases in the region, including in Bahrain or even in Gulf capitals that they see as aligning with Israel. At the very least, such attacks would completely derail peace talks and force the Saudis to act, plunging Yemen into a much more complex regional war.

Overall, there are no favorable options left for Saudi Arabia in Yemen. While the strategy of compartmentalizing the two issues has succeeded in protecting Riyadh thus far, this is only a temporary bandage absent an official peace agreement. The future of Yemen’s conflict is now inextricably linked to the upheaval in the Red Sea, and the country’s peace process must now take this uncomfortable reality into consideration.